GETTING HOOKED ON DAGA

Habit-forming fishing

By Mark Justham

(Originally published in the May 2025 issue of SKI-BOAT magazine)

WHEN Jan van Riebeeck’s troops landed in Cape Town in 1652 they found the sea off False Bay teeming with fish. Abundant among them were biggish silver fish that were easy to catch and very good eating, reminding the settlers of the kabeljauw (stockfish) found in the North Sea off the Netherlands (Holland).

This fish was named kabeljou in South Africa, a name that still remains today, although they also have a number of nicknames too: kob, daga salmon and boer-kabeljou. Internationally they’re known as drum.

Daga are still found in good numbers in most areas off Southern Africa’s coastline, from Angola all the way around the Cape right up into Moçambique. To my knowledge, this is the fish that occurs along the greatest length of Southern African coastline.

Before the ski-boating fraternity started targeting them around 1945, kob were mostly caught on rod and line off the beaches and rocky ledges. In those days of cane rods, Scarborough reels and cord line, distance casting was restricted. A cast into the shore break was achievable, so the shad and kob that frequented this shallow, turbulent water became the main target species and a source of extremely tasty food.

Scientists have since confirmed that daga hunt in murky, turbulent waters where they use their sense of smell and lateral line more than sight to find and catch small baitfish, crustaceans and, occasionally, squid, cuttlefish and octopus, according to Rudi van der Elst’s book, A Guide to the Common Sea Fishes of Southern Africa.

These fish are also often targeted at night, because their sense of smell and lateral line sense are not affected by the darkness and they continue to hunt, usually higher up in the water column than you would find them in the day.

With the advent of ski-boat fishing, anglers began to target daga at sea as well as in coastal estuaries where it’s believed that big, dark brown boer-kabeljou travel upstream to mate and disperse eggs. Many big specimens topping the 100 lb (45kg) mark are still caught primarily in the deep estuaries of the Eastern Cape such as that of the Breede River. The South African record currently stands at 73.5kg.

According to Rudi van der Elst’s A Guide to the Common Sea Fishes of Southern Africa, these fish are actually found at depths of up to 400 metres, but I haven’t ever caught them that deep.

Of specific interest to us ski-boaters is that daga like big pinnacles, reefs and especially wrecks and pipelines that run out to sea from the shore.

My experience targeting these fish is primarily from the KwaZulu-Natal coast, but I have also caught them out of East London and off the southern Cape coast.

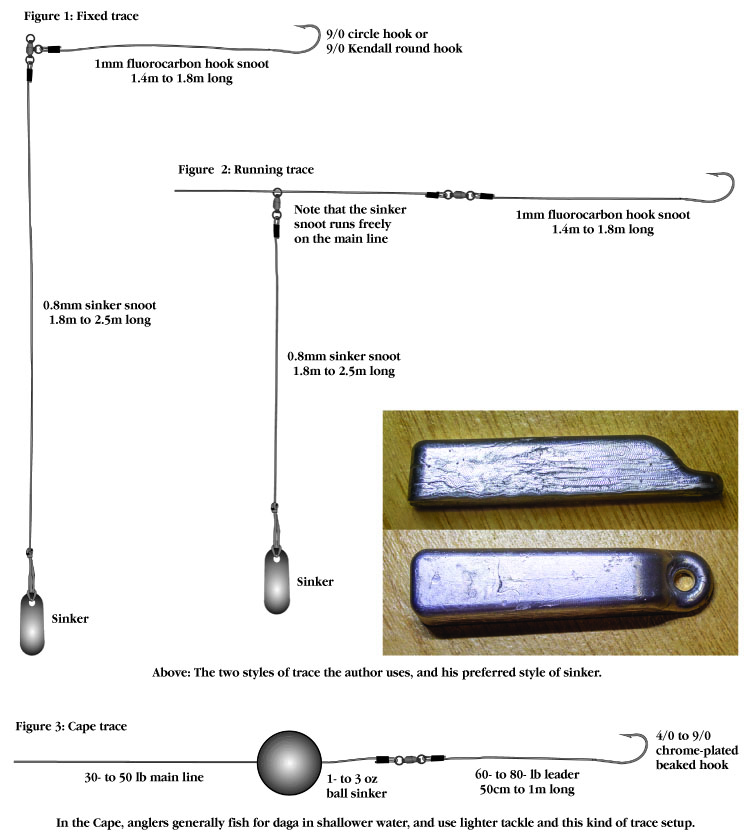

Fishing methods vary slightly, especially in the southern Cape where daga are generally targeted in shallower waters using a sliding sinker to a single hook with primarily squid/chokka and seekat pootjies (octopus tentacles) as bait, or else sardines or even a bomb bait of a mixture of both.

Angling for these magnificent fish takes some skill, and you will need to know a thing or two if you’re going to be successful, including which baits and traces to use, which reefs they frequent, how to anchor in the correct position, and which tides and times of the day to catch tthem on.

TIMES, TIDES AND PRESSURES

These fish can be caught at any time of the day, but they are certainly more active in the early morning just before the “Golden Glow”, and in the late afternoon into the early evening, as they are sensory feeders.

I’ve always preferred fishing one- to one-and-a-half hours before or after the turn of the tide.

I place great faith in my barometer, and if you don’t have one, I would suggest getting one and learning how it works and how barometric pressure affects fishing. The pressures are important, and a barometer will help you immensely.Basically if the barometric pressure is over 1 010 millibars it’s a good time to go fishing.

TRACE

TRACE

Everyone has their own favourite trace configuration, and this is mine. I start off with a three-way power swivel 2/0 X 3/0 1mm hook snooting. I use fluorocarbon. I generally use a 9/0 circle hook or a 9/0 Kendall round hook, then 0.8mm sinker snooting. (See Figure 1 overleaf.) I have always used a longer sinker snoot than hook snoot. My hook snoot is 1.4m to 1.8m long and my sinker snoot is 1.8m to 2.5m long.

If you are getting “pin holes” in your baits and they are dying it’s because the daga has mouthed it. If I find that happening, then I change to a running trace, using two single swivels, with the sinker snoot sliding on your leader, and your hook snoot tied directly to the leader, to reduce tension on the bait. (See Figure 2 overleaf.) Make sure you give slack to allow the daga to eat properly before you set the hook.

TACKLE

I still use a Geelbek Ski rod and a nine-inch Scarborough reel, but tackle has evolved and a lot of guys are now starting to use slow pitch rods and reels to catch daga.

RIGGING YOUR BAIT

RIGGING YOUR BAIT

Daga generally prefer a live mackerel here in KZN, but don’t write off a live maasbanker or shad. It all depends on what they are feeding on at the time. To determine what they are feeding on, each angler on the boat must try to go down with a different bait. Once someone gets a strike you can all change to the bait that is working.

When fishing for them during the daytime, I usually use dead baits, mackerel, mozzies, sardines or red eyes.

When rigging a live mackerel, I generally push the hook through the top lip, but not too deep into the bait’s head as you may kill it and then the action of the live bait will change, and you won’t get a pull. You need to keep your live bait swimming as naturally as possible.

Another way to rig the bait is to push the hook through the meat on the back of the live bait. Mozzies are good for this as they are a lot hardier than the mackerel.

When pinning a dead bait, I push the hook through both the bottom and top lip to ensure the hook has a better grip on the bait. There are also other ways of pinning dead baits by splitting the bait open and feeding the hook through from the back of the bait so that it protrudes through the bait’s head.

REEFS/WRECKS

I find that daga like to hang around wrecks or steel pipelines, and I believe they like to rub up against the steel to de-lice themselves. When it comes to reefs, they prefer certain reefs that carry bait on them as a food source and reefs that have certain corals or growth on them to attract the baitfish. That is what you need to look for on your sounder.

I have caught daga in depths of up to 100 metres, but I find they tend to stick to the shallower reefs/wrecks/pinnacles/ pipelines.

I’ve noticed over the years that during the day daga swim closer to the bottom of the ledge/reef, swimming almost on the sand, and as it starts getting darker, they will rise off the bottom and the showing on your sounder will rise.

ANCHORING

ANCHORING

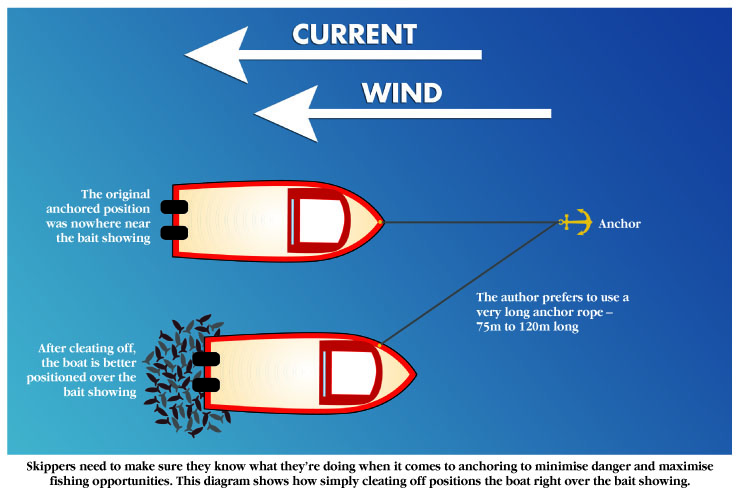

It’s critical that you anchor correctly when fishing for daga. You will need to know the structure of the seabed below you in order to know what anchor is best suited for the structure you are fishing on. This will depend on if you use a reef anchor or sand anchor.

You will need to sound around your structure or wreck for the showing of fish, and you will notice that the showing of fish will rise a few metres off the bottom once it gets dark. You will need to be on the showing, or you are wasting your time, and you are going to “hold pole”, so the position of your anchor is critical.

Please be careful if you’re anchoring in strong current, as this is dangerous, and is even more so if the current is running into the wind/swell which is very difficult to anchor in.

If you are fishing on a pipeline you will notice the showing coming and going on the sounder. This is because the daga will be swimming up and down the pipeline looking for the food source they want to eat as the current pushes it over the pipeline.

When it comes to pinnacles or reefs, they will swim around and come in to feed on the spot where the bait is.

On wrecks, they will swim around the wreck or even inside it, but will generally hang around the bait.

JUDGING THE FEED AND STRIKING

Daga, especially the big ones, are fussy feeders. Unlike their “cousins” the geelbek that don’t hesitate on the strike, resulting in a hit and wind scenario for the angler, catching daga demands a higher degree of angling technique and dexterity.

“Feel” is an absolute requirement, so don’t leave the rod in the gunnel and hope the fish will strike and hook itself.

They can be pernickety feeders, holding the bait – live or dead baits – tenderly in their mouths, then releasing the bait immediately if they feel any unusual tension on the bait. This leaves their telltale pin-like teeth marks on the bait.

When you do get a bite, knowing how much time to let the daga feed is important, and it all goes on the feel of the angler. Daga either pull you straight down or you will need to give them a few seconds to eat and swallow the bait, in which case you will wind into the fish, setting the hook for the best fight with beautiful head knocks as the daga tries to get the hook out.

The bigger fish will hold you on the bottom for a while before they tire out, and then you can start the slow wind up. The initial bite and setting the hook and the head knocks is something every angler will remember forever.

FIGHTING THE DAGA

Whether the daga one has hooked into is in shallow or deep water, it is generally a fair sized fish and needs to be fought with a good deal of finesse. Unlike a geelbek or half kob, where the normal strategy is crank and wind, daga need to be fought with skill and patience, and you’ll need to work it up gradually.

It is generally not a dirty fighter like an amberjack but it uses its weight and head nodding to attempt to free itself. When one gets it up a fair way, the barotrauma starts to affect its strength, but one still needs to work it upwards as it won’t just swim up to the surface.

GAFFING OR RELEASING

Handling the daga when it is brought alongside the boat, especially the really big ones, is not an easy exercise, especially if one is going to release it and gaffing is not an option.

I use a gloved hand to initially control the beast alongside my boat, getting a grip of the fish’s head by lifting the gill plate and sliding my hand in to grab its “handle” to stabilise the fish while deciding whether to remove the hook and release the daga or boat it.

Once the fish has broken water on the surface, it’s easy to tell if it has popped – if it has, the eyes will be protruding out of its head and the stomach/gall bladder will be hanging out its mouth. If this is the case, I would gaff it as its chances of surviving a release are very slim. If the fish hasn’t blown and is still strong, I would say it has a great chance of surviving, in which case you can release the daga by sending it back down to live another day.

I was fortunate enough to catch my personal best daga towards the end of last year – a beautiful specimen weighing in at 42.16kg.

Please remember that these fish are under huge pressure and get targeted quite hard, so limit your catch and stick to the limits, bearing in mind that these vary depending on where you are fishing .